Aleena was sixteen when she was first asked, “So, what do you want to become?” It sounded like a harmless, almost encouraging question, yet it landed with an unexpected heaviness. She smiled, paused, and replied, “I’m still thinking,” even though thinking was exactly what had been consuming her for years. Somewhere between childhood and adolescence, she had absorbed an unspoken rule: this was the age when decisions were supposed to lock life into place. Subjects chosen now would decide careers, careers would decide stability, and stability would decide worth. The problem was that Aleena did not yet know who she was, what she valued, or what kind of life would feel meaningful, and yet she felt rushed to choose a future she could not fully imagine.

Psychology has long acknowledged that this uncertainty is not a flaw but a natural part of development. Erik Erikson described adolescence as the stage of identity versus role confusion, emphasizing that questioning and experimentation are essential for building a coherent sense of self (Erikson, 1968). Confusion, in this sense, is not a sign of failure but of growth. Neuroscience supports this idea as well; research shows that the prefrontal cortex, responsible for long-term planning, impulse control, and complex decision-making, continues to mature into the mid-twenties (Steinberg, 2005). Despite this, social expectations rarely account for developmental reality. Hesitation is often interpreted as weakness, while certainty is praised as maturity, leaving adolescents feeling defective for doing exactly what their minds are designed to do.

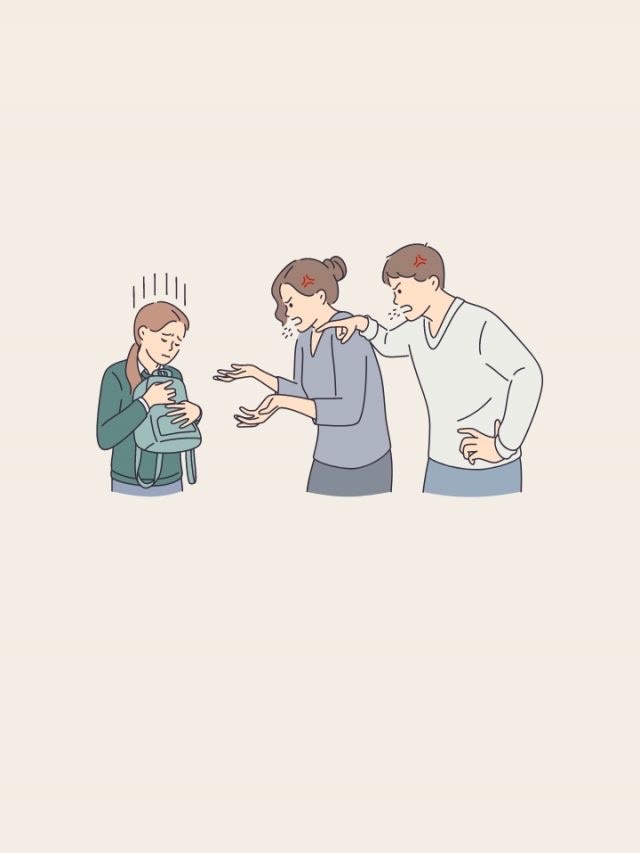

Aleena felt this pressure most strongly through expectations wrapped in encouragement. Phrases like “you have so much potential” or “this is the time to build your future” were meant to motivate, but they carried an invisible condition: potential must be proven through the right choices. Research on perceived parental and societal expectations suggests that when young people experience expectations as rigid or conditional, levels of anxiety, stress, and fear of failure increase significantly (Luthar & Becker, 2002). It is not ambition itself that becomes harmful, but the belief that love, approval, or security depend on choosing correctly. Aleena was not afraid of effort; she was afraid of choosing a path that would disappoint everyone and confirm her worst fears about herself.

Adding to this pressure was the overwhelming abundance of options. Aleena’s generation did not grow up with a single prescribed path; instead, they were presented with countless possibilities. Online, she saw peers becoming entrepreneurs, creators, therapists, researchers, and influencers, each narrative suggesting both success and urgency. Rather than feeling liberated, she felt paralysed. Psychologist Barry Schwartz describes this phenomenon as the paradox of choice, where an excess of options leads to greater anxiety, regret, and dissatisfaction (Schwartz, 2004). Research shows that individuals who strive to make the perfect decision, often referred to as “maximizers,” experience more stress and less satisfaction than those who accept decisions that are simply good enough. Aleena compared relentlessly, convinced that one wrong move could permanently close doors, and this pursuit of the perfect choice left her unable to choose at all.

What looked like indecision from the outside was, at its core, fear. Career psychology research indicates that career indecision is closely linked to anxiety, low self-confidence, and reduced decision-making self-efficacy, or the belief in one’s ability to make sound choices (Gati et al., 2011). For Aleena, the fear was not just about a course or a career, but about identity itself. She believed that choosing wrong would mean wasted years, irreversible regret, and a life that would never quite recover. This belief—that life is decided once and must be decided early—transformed normal uncertainty into something threatening.

One narrative that Aleena had never encountered was the idea that not knowing might actually be expected. Developmental psychologist Jeffrey Arnett introduced the concept of emerging adulthood, describing the late teens and twenties as a distinct life stage characterized by exploration, instability, and self-discovery (Arnett, 2000). According to this perspective, frequent changes in direction are not failures but natural features of development. Research suggests that individuals who are allowed time to explore different roles and paths often develop stronger self-knowledge and greater long-term satisfaction. Yet this framework rarely reaches adolescents, who are instead surrounded by urgency and comparison.

The perception that choices are permanent further intensifies anxiety. Studies on decision-making show that when choices are framed as irreversible and identity-defining, emotional distress increases and cognitive flexibility decreases (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000). In contrast, when choices are seen as revisable and experimental, people engage more openly and learn more effectively. Gradually, Aleena began to question a belief she had long taken for granted: what if choosing wrong did not ruin everything? What if decisions were not verdicts, but steps?

Instead of searching for a single, lifelong answer, Aleena started asking smaller questions. What could she try for a few months? What could experience teach her that endless thinking could not? Career development research highlights the importance of experiential exploration, such as short-term courses, internships, and volunteering, in building clarity and confidence (Savickas, 2013). These experiences provide real feedback, helping individuals understand both the world of work and their own preferences. As Aleena engaged in small, time-limited experiences, fear did not disappear, but it became manageable, replaced by a growing sense of self-trust.

The most difficult shift was internal. Aleena had learned to interpret uncertainty as personal inadequacy, a belief that quietly fed shame. Research on shame shows that when individuals equate confusion with failure, they are more likely to withdraw, ruminate, and avoid growth opportunities (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Reframing uncertainty as part of learning reduces shame and encourages engagement. Slowly, Aleena stopped asking what was wrong with her and began asking what she was learning. In that shift, indecision turned into curiosity.

Aleena’s experience reflects a broader cultural mismatch between what young people are developmentally capable of and what they are expected to deliver. Educational systems and social narratives demand premature certainty, while psychological science consistently shows that identity formation is nonlinear and that clarity often follows experience rather than preceding it. Adolescents are not meant to have life figured out; they are meant to explore, revise, and grow. Not knowing is not a sign of failure, but evidence of becoming, and perhaps the greatest disservice we do to young people is convincing them otherwise.

Touch of Peace Mental Health Care Services Pvt. Ltd. Building an inclusive haven, where emotional well-being is woven into daily life.

Copyright © 2024 Touch Of Peace Care | Made With ❤️ Viba Digital Agency.